假基因

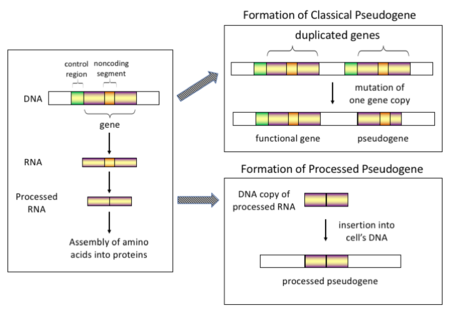

一些假基因形成的學說,左圖表示從基因到蛋白質的過程,右上圖表示假基因形成的傳統學說:一個基因發生了複製,隨後一個基因發生突變,成爲假基因。一個新的學說認爲,假基因是基因轉錄的RNA逆轉錄並整合到DNA上形成的[1][2]

假基因(Pseudogenes,Pseudo-意爲「假」)是一類染色體上的基因片段。假基因的序列通常與對應的基因相似,但至少是喪失了一部分功能,如基因不能表達或編碼的蛋白質沒有功能[3]。

一般認爲,假基因最初是功能對生物生存並非必要的基因。隨着突變的積累,出現編碼區提前出現終止密碼子、移碼突變等情況,逐漸變爲無功能的假基因。另外,拷貝數變異(Copy-number variation, CNV)也可能產生假基因。在拷貝數變異中,1kb(千鹼基對)以上的DNA片段會發生複製或刪除[4]。一部分假基因既沒有內含子,也沒有啓動子(這種啓動子被認爲是通過mRNA的逆轉錄轉移到染色體上的,稱爲「加工」假基因(processed pseudogenes))[5],但部分假基因仍然擁有一些與正常基因相同的特徵,比如擁有CpG島等啓動子、RNA剪接位點等。

假基因這一名詞是由雅克(Jacq)等人於1977年最早提出的[6]。長期以來生物學家們認爲假基因是沒有功能的垃圾DNA,惟近年來的研究還表明假基因和其他非編碼片段一樣,擁有調控基因表達的功能。假基因的調控作用對維持生物體的生理活動有着重要意義,一部分假基因在某些疾病的發展中也扮演着重要角色[7]。

在進化生物學研究中,假基因序列分析一直是研究者獲知生物進化歷程的手段。假基因一般會擁有一些源基因的特徵。按照進化論的觀點,兩個親緣關係較近的物種擁有同一祖先。對假基因進行序列比對、分析,即可驗證兩物種是否擁有同一祖先,並能計算出兩物種開始分離的時間(結果能精確到百萬年)。

目录

1 特性

2 类型及成因

2.1 Processed

2.2 Non-processed

2.3 Unitary pseudogenes

2.4 Pseudo-pseudogenes

3 假基因功能的例子

4 细菌假基因

5 參見

6 參考

7 拓展閱讀

8 外部連結

特性

已隱藏部分未翻譯部分,歡迎參與翻譯。

Pseudogenes are usually characterized by a combination of homology to a known gene and loss of some functionality. That is, although every pseudogene has a DNA sequence that is similar to some functional gene, they are usually unable to produce functional final protein products.[8] Pseudogenes are sometimes difficult to identify and characterize in genomes, because the two requirements of homology and loss of functionality are usually implied through sequence alignments rather than biologically proven.

- Homology is implied by sequence identity between the DNA sequences of the pseudogene and parent gene. After aligning the two sequences, the percentage of identical base pairs is computed. A high sequence identity means that it is highly likely that these two sequences diverged from a common ancestral sequence (are homologous), and highly unlikely that these two sequences have evolved independently (see Convergent evolution).

- Nonfunctionality can manifest itself in many ways. Normally, a gene must go through several steps to a fully functional protein: Transcription, pre-mRNA processing, translation, and protein folding are all required parts of this process. If any of these steps fails, then the sequence may be considered nonfunctional. In high-throughput pseudogene identification, the most commonly identified disablements are premature stop codons and frameshifts, which almost universally prevent the translation of a functional protein product.

Pseudogenes for RNA genes are usually more difficult to discover as they do not need to be translated and thus do not have "reading frames".

Pseudogenes can complicate molecular genetic studies. For example, amplification of a gene by PCR may simultaneously amplify a pseudogene that shares similar sequences. This is known as PCR bias or amplification bias. Similarly, pseudogenes are sometimes annotated as genes in genome sequences.

Processed pseudogenes often pose a problem for gene prediction programs, often being misidentified as real genes or exons. It has been proposed that identification of processed pseudogenes can help improve the accuracy of gene prediction methods.[9]

Recently 140 human pseudogenes have been shown to be translated.[10] However, the function, if any, of the protein products is unknown.

类型及成因

根据不同的起源机制和特点,假基因可大致分为如下四类:

已隱藏部分未翻譯部分,歡迎參與翻譯。

Processed

Processed pseudogene production

Processed (or retrotransposed) pseudogenes. In higher eukaryotes, particularly mammals, retrotransposition is a fairly common event that has had a huge impact on the composition of the genome. For example, somewhere between 30–44% of the human genome consists of repetitive elements such as SINEs and LINEs (see retrotransposons).[11][12] In the process of retrotransposition, a portion of the mRNA or hnRNA transcript of a gene is spontaneously reverse transcribed back into DNA and inserted into chromosomal DNA. Although retrotransposons usually create copies of themselves, it has been shown in an in vitro system that they can create retrotransposed copies of random genes, too.[13] Once these pseudogenes are inserted back into the genome, they usually contain a poly-A tail, and usually have had their introns spliced out; these are both hallmark features of cDNAs. However, because they are derived from an RNA product, processed pseudogenes also lack the upstream promoters of normal genes; thus, they are considered "dead on arrival", becoming non-functional pseudogenes immediately upon the retrotransposition event.[14] However, these insertions occasionally contribute exons to existing genes, usually via alternatively spliced transcripts.[15] A further characteristic of processed pseudogenes is common truncation of the 5' end relative to the parent sequence, which is a result of the relatively non-processive retrotransposition mechanism that creates processed pseudogenes.[16] Processed pseudogenes are continually being created in primates.[17] Human populations, for example, have distinct sets of processed pseudogenes across its individuals.[18]

Non-processed

One way a pseudogene may arise

Non-processed (or duplicated) pseudogenes. Gene duplication is another common and important process in the evolution of genomes. A copy of a functional gene may arise as a result of a gene duplication event caused by homologous recombination at, for example, repetitive sine sequences on misaligned chromosomes and subsequently acquire mutations that cause the copy to lose the original gene's function. Duplicated pseudogenes usually have all the same characteristics as genes, including an intact exon-intron structure and regulatory sequences. The loss of a duplicated gene's functionality usually has little effect on an organism's fitness, since an intact functional copy still exists. According to some evolutionary models, shared duplicated pseudogenes indicate the evolutionary relatedness of humans and the other primates.[19] If pseudogenization is due to gene duplication, it usually occurs in the first few million years after the gene duplication, provided the gene has not been subjected to any selection pressure.[20] Gene duplication generates functional redundancy and it is not normally advantageous to carry two identical genes. Mutations that disrupt either the structure or the function of either of the two genes are not deleterious and will not be removed through the selection process. As a result, the gene that has been mutated gradually becomes a pseudogene and will be either unexpressed or functionless. This kind of evolutionary fate is shown by population genetic modeling[21][22] and also by genome analysis.[20][23] According to evolutionary context, these pseudogenes will either be deleted or become so distinct from the parental genes so that they will no longer be identifiable. Relatively young pseudogenes can be recognized due to their sequence similarity.[24]

Unitary pseudogenes

2 ways a pseuogene may be produced

Various mutations (such as indels and nonsense mutations) can prevent a gene from being normally transcribed or translated, and thus the gene may become less- or non-functional or "deactivated". These are the same mechanisms by which non-processed genes become pseudogenes, but the difference in this case is that the gene was not duplicated before pseudogenization. Normally, such a pseudogene would be unlikely to become fixed in a population, but various population effects, such as genetic drift, a population bottleneck, or, in some cases, natural selection, can lead to fixation. The classic example of a unitary pseudogene is the gene that presumably coded the enzyme L-gulono-γ-lactone oxidase (GULO) in primates. In all mammals studied besides primates (except guinea pigs), GULO aids in the biosynthesis of ascorbic acid (vitamin C), but it exists as a disabled gene (GULOP) in humans and other primates.[25][26] Another more recent example of a disabled gene links the deactivation of the caspase 12 gene (through a nonsense mutation) to positive selection in humans.[27]

It has been shown that processed pseudogenes accumulate mutations faster than non-processed pseudogenes.[28]

Pseudo-pseudogenes

The rapid proliferation of DNA sequencing technologies has led to the identification of many apparent pseudogenes using gene prediction techniques. Pseudogenes are often identified by the appearance of a premature stop codon in a predicted mRNA sequence, which would, in theory, prevent synthesis (translation) of the normal protein product of the original gene. There have been some reports of translational readthrough of such premature stop codons in mammals, as reviewed in the "Translational readthrough" section of the stop codon article. As alluded to in the figure above, a small amount of the protein product of such readthrough may still be recognizable and function at some level. If so, the pseudogene can be subject to natural selection. That appears to have happened during the evolution of Drosophila species, as described next.

Drosophila melanogaster

In 2016 it was reported that 4 predicted pseudogenes in multiple Drosophila species actually encode proteins with biologically important functions,[29] "suggesting that such 'pseudo-pseudogenes' could represent a widespread phenomenon". For example, the functional protein (an olfactory receptor) is found only in neurons. This finding of tissue-specific biologically-functional genes that could have been dismissed as pseudogenes by in silico analysis complicates the analysis of sequence data. As of 2012, it appeared that there are approximately 12,000–14,000 pseudogenes in the human genome,[30] almost comparable to the oft-cited approximate value of 20,000 genes in our genome. The current work may also help to explain why we are able to live with 20 to 100 putative homozygous loss of function mutations in our genomes.[31]

Through reanalysis of over 50 million peptides generated from the human proteome and separated by mass spectrometry, it now (2016) appears that there are at least 19,262 human proteins produced from 16,271 genes or clusters of genes. From this analysis, 8 new protein coding genes that were previously considered pseudogenes were identified.[32]

假基因功能的例子

- The term "pseudo-pseudogene" was coined in the publication that investigated the gene in the chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptor Ir75a of Drosophila sechellia, which bears a premature termination codon (PTC) and was thus classified as a pseudogene based on that in silico analysis. However, in vivo the D. sechellia Ir75a locus produces a functional receptor, owing to translational read-through of the PTC. Read-through is detected only in neurons and depends on the nucleotide sequence downstream of the PTC.[29]

- The Drosophila jingwei gene produces a functional alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme in vivo.[33] However, previous in silico analysis classified it as a processed pseudogene.[34] The evolution of this gene has been discussed.[35]

- A human processed pseudogene of phosphoglycerate mutase was initially reported by interpretation of both in silico and experimental evidence.[36] That pseudogene was investigated more fully by another group, which found convincing evidence that it was a functional gene,[37] which is now named PGAM4. The gene is expressed in the testes and polymorphisms in that gene appear to account for about 5% of cases of male infertility.[38]

- siRNAs. Some endogenous siRNAs appear to be derived from pseudogenes, and thus some pseudogenes play a role in regulating protein-coding transcripts, as reviewed.[39] One of the many examples is psiPPM1K. Processing of RNAs transcribed from psiPPM1K yield siRNAs that can act to suppress the most common type of liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma.[40] This and much other research has led to considerable excitement about the possibility of targeting pseudogenes with/as therapeutic agents[41]

- Some piRNAs are derived from pseudogenes located in piRNA clusters.[42] Those piRNAs regulate genes via the piRNA pathway in mammalian testes and are crucial for limiting transposable element damage to the genome.[43]

BRAF pseudogene acts as a ceRNA

- There are many reports of pseudogene transcripts acting as microRNA decoys. Perhaps the earliest definitive example of such a pseudogene involved in cancer is the pseudogene of BRAF. The BRAF gene is a proto-oncogene that, when mutated, is associated with many cancers. Normally, the amount of BRAF protein is kept under control in cells through the action of miRNA. In normal situations, the amount of RNA from BRAF and the pseudogene BRAFP1 compete for miRNA, but the balance of the 2 RNAs is such that cells grow normally. However, when BRAFP1 RNA expression is increased (either experimentally or by natural mutations), less miRNA is available to control the expression of BRAF, and the increased amount of BRAF protein causes cancer.[44] This sort of competition for regulatory elements by RNAs that are endogenous to the genome has given rise to the term ceRNA.

- The PTEN gene is a known tumor suppressor gene. The PTEN pseudogene, PTENP1 is a processed pseudogene that is very similar in its genetic sequence to the wild-type gene. However, PTENP1 has a missense mutation which eliminates the codon for the initiating methionine and thus prevents translation of the normal PTEN protein.[45] In spite of that, PTENP1 appears to play a role in oncogenesis. The 3' UTR of PTENP1 mRNA functions as a decoy of PTEN mRNA by targeting micro RNAs due to its similarity to the PTEN gene, and overexpression of the 3' UTR resulted in an increase of PTEN protein level.[46] That is, overexpression of the PTENP1 3' UTR leads to increased regulation and suppression of cancerous tumors. The biology of this system is basically the inverse of the BRAF system described above.

- Pseudogenes can, over evolutionary time scales, participate in gene conversion and other mutational events that may give rise to new or newly-functional genes. This has led to the concept, used in a major review from 2003, that pseudogenes could be viewed as potogenes: potential genes for evolutionary diversification.[47]

细菌假基因

细菌基因组中也存在假基因[48]。这些拥有假基因的细菌通常为共生或细胞内寄生,因此它们不需要一些生活在外界复杂环境中的细菌所必须的基因。一个极端的例子是麻风病的病原体--麻风杆菌(Mycobacterium leprae)的基因组,已报道有1,133个假基因约占其转录组的50%[49]。

參見

- 逆轉座子

- RNA干擾

參考

^ Max EE. Plagiarized Errors and Molecular Genetics. Creation Evolution Journal. 1986, 6 (3): 34–46.

^ Chandrasekaran C, Betrán E. Origins of new genes and pseudogenes.. Nature Education. 2008, 1 (1): 181.

^ Vanin EF. Processed pseudogenes: characteristics and evolution. Annual Review of Genetics. 1985, 19: 253–72. PMID 3909943. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.19.120185.001345.

^ Chang Y, Stuart A, 等. Antigen presenting genes and genomic copy number variations in the Tasmanian devil MHC. BMC Genomics. 2012, 13:87. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-13-87.

^ Herron JC, Freeman S. Evolutionary analysis 4th. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. 2007. ISBN 978-0-13-227584-2.

^ Jacq C, Miller JR, Brownlee GG. A pseudogene structure in 5S DNA of Xenopus laevis. Cell. September 1977, 12 (1): 109–20. PMID 561661. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(77)90189-1.

^ Xiao-Jie L, Ai-Mei G, Li-Juan J, Jiang X. Pseudogene in cancer: real functions and promising signature. Journal of Medical Genetics. January 2015, 52 (1): 17–24. PMID 25391452. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102785.

^ Mighell AJ, Smith NR, Robinson PA, Markham AF. Vertebrate pseudogenes. FEBS Letters. February 2000, 468 (2–3): 109–14. PMID 10692568. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01199-6.

^ van Baren MJ, Brent MR. Iterative gene prediction and pseudogene removal improves genome annotation. Genome Research. May 2006, 16 (5): 678–85. PMC 1457044. PMID 16651666. doi:10.1101/gr.4766206.

^ Kim, MS; 等. A draft map of the human proteome.. Nature. 2014, 509: 575–581. PMC 4403737. PMID 24870542. doi:10.1038/nature13302. 引文格式1维护:显式使用等标签 (link)

^ Jurka J. Evolutionary impact of human Alu repetitive elements. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. December 2004, 14 (6): 603–8. PMID 15531153. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2004.08.008.

^ Dewannieux M, Heidmann T. LINEs, SINEs and processed pseudogenes: parasitic strategies for genome modeling. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2005, 110 (1–4): 35–48. PMID 16093656. doi:10.1159/000084936.

^ Dewannieux M, Esnault C, Heidmann T. LINE-mediated retrotransposition of marked Alu sequences. Nature Genetics. September 2003, 35 (1): 41–8. PMID 12897783. doi:10.1038/ng1223.

^ Graur D, Shuali Y, Li WH. Deletions in processed pseudogenes accumulate faster in rodents than in humans. Journal of Molecular Evolution. April 1989, 28 (4): 279–85. PMID 2499684. doi:10.1007/BF02103423.

^ Baertsch R, Diekhans M, Kent WJ, Haussler D, Brosius J. Retrocopy contributions to the evolution of the human genome. BMC Genomics. October 2008, 9: 466. PMC 2584115. PMID 18842134. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-466.

^ Pavlícek A, Paces J, Zíka R, Hejnar J. Length distribution of long interspersed nucleotide elements (LINEs) and processed pseudogenes of human endogenous retroviruses: implications for retrotransposition and pseudogene detection. Gene. October 2002, 300 (1–2): 189–94. PMID 12468100. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01047-8.

^ Navarro FC, Galante PA. A Genome-Wide Landscape of Retrocopies in Primate Genomes. Genome Biology and Evolution. July 2015, 7 (8): 2265–75. PMC 4558860. PMID 26224704. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv142.

^ Schrider DR, Navarro FC, Galante PA, Parmigiani RB, Camargo AA, Hahn MW, de Souza SJ. Gene copy-number polymorphism caused by retrotransposition in humans. PLoS Genetics. 2013-01-24, 9 (1): e1003242. PMC 3554589. PMID 23359205. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003242.

^ Max EE. Plagiarized Errors and Molecular Genetics. TalkOrigins Archive. 2003-05-05 [2008-07-22].

^ 20.020.1 Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. November 2000, 290 (5494): 1151–5. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1151L. PMID 11073452. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1151.

^ Walsh JB. How often do duplicated genes evolve new functions?. Genetics. January 1995, 139 (1): 421–8. PMC 1206338. PMID 7705642.

^ Lynch M, O'Hely M, Walsh B, Force A. The probability of preservation of a newly arisen gene duplicate. Genetics. December 2001, 159 (4): 1789–804. PMC 1461922. PMID 11779815.

^ Harrison PM, Hegyi H, Balasubramanian S, Luscombe NM, Bertone P, Echols N, Johnson T, Gerstein M. Molecular fossils in the human genome: identification and analysis of the pseudogenes in chromosomes 21 and 22. Genome Research. February 2002, 12 (2): 272–80. PMC 155275. PMID 11827946. doi:10.1101/gr.207102.

^ Zhang J. Evolution by gene duplication: an update.. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2003, 18 (6): 292–298. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00033-8.

^ Nishikimi M, Kawai T, Yagi K. Guinea pigs possess a highly mutated gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the key enzyme for L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis missing in this species. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. October 1992, 267 (30): 21967–72. PMID 1400507.

^ Nishikimi M, Fukuyama R, Minoshima S, Shimizu N, Yagi K. Cloning and chromosomal mapping of the human nonfunctional gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the enzyme for L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis missing in man. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. May 1994, 269 (18): 13685–8. PMID 8175804.

^ Xue Y, Daly A, Yngvadottir B, Liu M, Coop G, Kim Y, Sabeti P, Chen Y, Stalker J, Huckle E, Burton J, Leonard S, Rogers J, Tyler-Smith C. Spread of an inactive form of caspase-12 in humans is due to recent positive selection. American Journal of Human Genetics. April 2006, 78 (4): 659–70. PMC 1424700. PMID 16532395. doi:10.1086/503116.

^ Zheng D, Frankish A, Baertsch R, Kapranov P, Reymond A, Choo SW, Lu Y, Denoeud F, Antonarakis SE, Snyder M, Ruan Y, Wei CL, Gingeras TR, Guigó R, Harrow J, Gerstein MB. Pseudogenes in the ENCODE regions: consensus annotation, analysis of transcription, and evolution. Genome Research. June 2007, 17 (6): 839–51. PMC 1891343. PMID 17568002. doi:10.1101/gr.5586307.

^ 29.029.1 Prieto-Godino LL, Rytz R, Bargeton B, Abuin L, Arguello JR, Peraro MD, Benton R. Olfactory receptor pseudo-pseudogenes. Nature. November 2016, 539 (7627): 93–97. PMC 5164928. PMID 27776356. doi:10.1038/nature19824.

^ Pei B, Sisu C, Frankish A, Howald C, Habegger L, Mu XJ, Harte R, Balasubramanian S, Tanzer A, Diekhans M, Reymond A, Hubbard TJ, Harrow J, Gerstein MB. The GENCODE pseudogene resource. Genome Biology. September 2012, 13 (9): R51. PMC 3491395. PMID 22951037. doi:10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r51.

^ MacArthur DG, Balasubramanian S, Frankish A, Huang N, Morris J, Walter K, 等. A systematic survey of loss-of-function variants in human protein-coding genes. Science. February 2012, 335 (6070): 823–8. PMC 3299548. PMID 22344438. doi:10.1126/science.1215040.

^ Wright JC, Mudge J, Weisser H, Barzine MP, Gonzalez JM, Brazma A, Choudhary JS, Harrow J. Improving GENCODE reference gene annotation using a high-stringency proteogenomics workflow. Nature Communications. June 2016, 7: 11778. PMC 4895710. PMID 27250503. doi:10.1038/ncomms11778.

^ Long M, Langley CH. Natural selection and the origin of jingwei, a chimeric processed functional gene in Drosophila. Science. April 1993, 260 (5104): 91–5. Bibcode:1993Sci...260...91L. PMID 7682012. doi:10.1126/science.7682012.

^ Jeffs P, Ashburner M. Processed pseudogenes in Drosophila. Proceedings. Biological Sciences. May 1991, 244 (1310): 151–9. PMID 1679549. doi:10.1098/rspb.1991.0064.

^ Wang W, Zhang J, Alvarez C, Llopart A, Long M. The origin of the Jingwei gene and the complex modular structure of its parental gene, yellow emperor, in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular Biology and Evolution. September 2000, 17 (9): 1294–301. PMID 10958846. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026413.

^ Dierick HA, Mercer JF, Glover TW. A phosphoglycerate mutase brain isoform (PGAM 1) pseudogene is localized within the human Menkes disease gene (ATP7 A). Gene. October 1997, 198 (1–2): 37–41. PMID 9370262. doi:10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00289-8.

^ Betrán E, Wang W, Jin L, Long M. Evolution of the phosphoglycerate mutase processed gene in human and chimpanzee revealing the origin of a new primate gene. Molecular Biology and Evolution. May 2002, 19 (5): 654–63. PMID 11961099. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004124.

^ Okuda H, Tsujimura A, Irie S, Yamamoto K, Fukuhara S, Matsuoka Y, Takao T, Miyagawa Y, Nonomura N, Wada M, Tanaka H. A single nucleotide polymorphism within the novel sex-linked testis-specific retrotransposed PGAM4 gene influences human male fertility. PloS One. 2012, 7 (5): e35195. PMC 3348931. PMID 22590500. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035195.

^ Chan WL, Chang JG. Pseudogene-derived endogenous siRNAs and their function. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2014, 1167: 227–39. PMID 24823781. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0835-6_15.

^ Chan WL, Yuo CY, Yang WK, Hung SY, Chang YS, Chiu CC, Yeh KT, Huang HD, Chang JG. Transcribed pseudogene ψPPM1K generates endogenous siRNA to suppress oncogenic cell growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nucleic Acids Research. April 2013, 41 (6): 3734–47. PMC 3616710. PMID 23376929. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt047.

^ Roberts TC, Morris KV. Not so pseudo anymore: pseudogenes as therapeutic targets. Pharmacogenomics. December 2013, 14 (16): 2023–34. PMC 4068744. PMID 24279857. doi:10.2217/pgs.13.172.

^ Olovnikov I, Le Thomas A, Aravin AA. A framework for piRNA cluster manipulation. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2014, 1093: 47–58. PMID 24178556. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-694-8_5.

^ Siomi MC, Sato K, Pezic D, Aravin AA. PIWI-interacting small RNAs: the vanguard of genome defence. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. April 2011, 12 (4): 246–58. PMID 21427766. doi:10.1038/nrm3089.

^ Karreth FA, Reschke M, Ruocco A, Ng C, Chapuy B, Léopold V, Sjoberg M, Keane TM, Verma A, Ala U, Tay Y, Wu D, Seitzer N, Velasco-Herrera Mdel C, Bothmer A, Fung J, Langellotto F, Rodig SJ, Elemento O, Shipp MA, Adams DJ, Chiarle R, Pandolfi PP. The BRAF pseudogene functions as a competitive endogenous RNA and induces lymphoma in vivo. Cell. April 2015, 161 (2): 319–32. PMID 25843629. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.043.

^ Dahia PL, FitzGerald MG, Zhang X, Marsh DJ, Zheng Z, Pietsch T, von Deimling A, Haluska FG, Haber DA, Eng C. A highly conserved processed PTEN pseudogene is located on chromosome band 9p21. Oncogene. May 1998, 16 (18): 2403–6. PMID 9620558. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201762.

^ Poliseno L, Salmena L, Zhang J, Carver B, Haveman WJ, Pandolfi PP. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature. June 2010, 465 (7301): 1033–8. PMC 3206313. PMID 20577206. doi:10.1038/nature09144.

^ Balakirev ES, Ayala FJ. Pseudogenes: are they "junk" or functional DNA?. Annual Review of Genetics. 2003, 37: 123–51. PMID 14616058. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.37.040103.103949.

^ Goodhead I, Darby AC. Taking the pseudo out of pseudogenes. Current Opinion in Microbiology. February 2015, 23: 102–9. PMID 25461580. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.012.

^ Williams DL, Slayden RA, Amin A, Martinez AN, Pittman TL, Mira A, Mitra A, Nagaraja V, Morrison NE, Moraes M, Gillis TP. Implications of high level pseudogene transcription in Mycobacterium leprae. BMC Genomics. August 2009, 10: 397. PMC 2753549. PMID 19706172. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-397.

拓展閱讀

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Gerstein M, Zheng D. The real life of pseudogenes. Scientific American. August 2006, 295 (2): 48–55. PMID 16866288. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0806-48.

Torrents D, Suyama M, Zdobnov E, Bork P. A genome-wide survey of human pseudogenes. Genome Research. December 2003, 13 (12): 2559–67. PMC 403797. PMID 14656963. doi:10.1101/gr.1455503.

Bischof JM, Chiang AP, Scheetz TE, Stone EM, Casavant TL, Sheffield VC, Braun TA. Genome-wide identification of pseudogenes capable of disease-causing gene conversion. Human Mutation. June 2006, 27 (6): 545–52. PMID 16671097. doi:10.1002/humu.20335.

外部連結

- Pseudogene interaction database, miRNA-pseudogene and protein-pseudogene interaction maps database

- Yale University pseudogene database

Hoppsigen database (homologous processed pseudogenes)